Interview with Author Barbara Joan Scott: Conquering the Demons of Self-Doubt

Busy Women on Writing Books

This is another instalment in a new interview series on writing, profiling women writers who’ve written and published books while also working, parenting, volunteering, caring for family, attending school, and ALL OF THE THINGS.

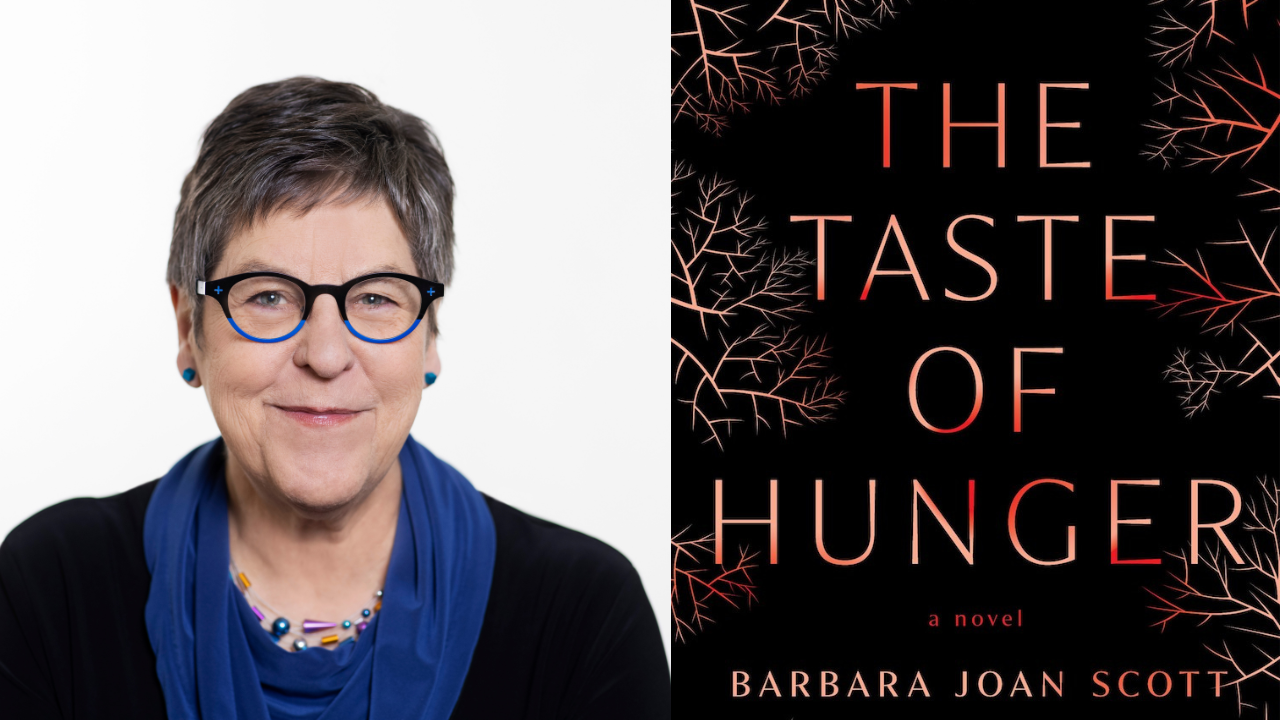

This week, I'm pleased to introduce you to an amazingly gifted writer, Barbara Joan Scott.

Barbara Joan Scott has had the great good fortune to be able to devote most of her adult working life to creative writing, as an author, editor, and teacher. Her first book, The Quick, won the City of Calgary W. O. Mitchell Book Prize, and the WGA Howard O’Hagan Award for Best Collection of Short Fiction, and was shortlisted for the WGA Henry Kreisel Award for Best First Book. In 2015 she received the Lois Hole Award for Editorial Excellence and in 2021 her essay “Black Diamond” won the WGA’s Jon Whyte Award.

The Taste of Hunger is her first novel. In his review for The Miramichi Reader, Ian Colford says: “Barbara Joan Scott tells a story filled with fierce passion, wayward desire and thwarted dreams, a story that skirts the edges of melodrama without making the plunge. The Taste of Hunger also provides a compulsive read and leaves us pondering the darkness that resides in every human heart.”

I know how amazing you are, but please let everyone else know a bit about yourself and the books you’ve written thus far. Own it and brag a bit for us!

My first book, The Quick, a collection of short stories, was shortlisted for the Writers’ Guild of Alberta Award for Best First Book, won the WGA Howard O’Hagan award for Best Collection of Fiction, and won the W.O. Mitchell City of Calgary Award for Best Book.

It was very well received by reviewers, appearing on the Toronto Star’s list of ‘must reads,’ where Stephen Finucan wrote: “Confident, subtle and visceral, The Quick should not be missed.” Audrey Andrews in The Calgary Herald wrote: “[These stories] reward slow, careful reading. … their substance, what they mean, is offered by a writer who is compassionate, knowing, wise. They are what stories ought to be, and The Quick is cause for celebration.”

My second book and first novel, The Taste of Hunger, was released Sept. 1 of this year and reaction has been very favourable. Ian Colford in his Miramichi Reader review wrote: “Barbara Joan Scott tells a story filled with fierce passion, wayward desire and thwarted dreams, a story that skirts the edge of melodrama without making the plunge. The Taste of Hunger also provides a compulsive read and leaves us pondering the darkness that resides in every human heart.”

The consensus from responses I’ve had from readers across the board seems to be that once it’s been picked up, it's almost impossible to put down. Since I wanted to write a literary page-turner, this makes me very happy.

What’s your current writing routine? Has it always been like this? What about it might be different for you now than in the past?

My current writing routine is being reshaped. During the pandemic, when I had so few outside obligations, I wrote at various times of the day, not worrying too much about a routine. I was editing my novel, so I found that tackling it at odd times in the day, sneaking up on it as it were, was helpful.

But now, of course, various obligations are creeping back in, so I’m trying to get back to my usual routine of getting to the computer at about 8 a.m., journaling, reading something like Virginia Woolf’s diaries to remind me of what I love about writing, then getting to some project or other at the computer.

I find that morning energy is better when I’m developing new ideas. By noon I’m done for the writing day. I try not to be too hard on myself, which is different from when I first started out.

One of my early creative writing teachers was an extremely busy academic who could only find time to write at 5 a.m. so of course all of us students thought there was something magical about this, that if we didn’t do the same we weren’t ‘real’ writers. But I am brain dead at 5 a.m.! Pretty soon I realized you have to create a routine that works for you.

When I was teaching at the then Alberta College of Art and Design, I arranged to teach only in the afternoon and evening. That left my mornings free for writing. Others may only be able to write on the weekends, or in the evenings.

I think the important thing is to find what works for you and then stick to it, and to realize that what works for one project or at one time in your life may not work at another: the only real rule is to find what gets you to your project.

One very important part of my routine is not to answer the phone while I’m at the computer. Also to avoid email.

Tell us the story of when you first got published. What was special about that experience for you?

Oddly enough I don’t remember how I reacted when my first story got published. But when I found out that my first book was going to be published I couldn’t stop smiling for two months.

Then I had a brief moment when I thought, “Well, I guess I’m calming down about it” but no: I smiled for another two months straight.

J. K. Rowling had the same reaction, saying in an interview that there is no greater happiness than finding out your first book is going to be published. The really funny thing is that my publisher, Jan Geddes of Cormorant Books, was in Ontario and when I phoned (in the aftermath of Ontario’s dreadful ice storm, during which they’d declared a state of emergency and called in the army) to find out if the answer was to be (as I was pretty sure it was) No, Jan told me she was taking it and I was stunned.

After I hung up the phone I thought, Maybe the ice storm has addled her brain. I didn’t really believe her until I got the contract. Every single writer reading this should have that moment. The only thing that compares is when I discovered I was in love with my now husband. And it’s a tie.

When did you start “getting serious” about writing and what did that look like for you?

I’ve always loved teaching English Lit and creative writing, and editing fiction and creative non-fiction, but eventually I had to acknowledge that for me these activities require the same energy as my own writing.

The moment of truth came when I was in Toronto as the editor of an author whose book was shortlisted for the Amazon First Novel Award. It was the second year in a row that one of my authors had been shortlisted, and the year before I’d won an award for editorial excellence. I looked around the room and it wasn’t so much that I wanted to be up for the award, I just wanted to be one of the writers, not one of the editors.

No matter how deeply satisfying it was to help others achieve their dreams of making their books as good as they could be, it was time to put my own writing first, and make my novel the best it could be. Also, I wasn’t getting any younger. So I retired from editing (I had stopped teaching some time before) and devoted myself to my novel: and now I am one of the authors.

A similar thing happened many years earlier when as an editor of a book submitted to a small press I was talking with the press’s editor who said she’d quit writing because, well, writing is so hard, it’s so much easier to be an editor, don’t you agree? Right then I devoted myself to finishing The Quick. And while it did win and get shortlisted for awards, the real delight came in holding it in my hands, knowing I had conquered the demons of self-doubt that for me are an inevitable part of the process.

I do realize that younger writers are likely not able to quit their day jobs, but I think that ultimately taking yourself seriously requires facing some hard truths about yourself, asking what you can drop from your life, even if it opens up only a few hours, to make room for the most important thing: your writing life.

What have you had going on in your life over the years that wasn’t writing and may have made finding time to write challenging? What strategies did you use to overcome those obstacles and get the writing done?

I’ve mentioned one of the challenges in the previous answer: the way teaching and editing used up the creative energy I needed to tackle my own work. But the other, greater issue was psychological and it surfaced very strongly when I brought out my first book. I was raised by hyper-critical parents: if I failed that was terrible, but if I succeeded they wanted to make sure I didn’t get too big for my boots so they would swiftly bring me down a peg.

When The Quick did well for a short story collection from a small press, since I had prepared for failure, even the modest success threw me for a loop. If I shortlisted for an award I didn’t get, I had failed; if I won an award, the critical voices started up in my head.

At the same time, my mother and sister-in-law were both very ill and the tensions around that, as well as the guilt I felt as I tried to protect at least some of my writing time, threw me into a deep depression for a number of years. The way I dealt with that was to get therapy at various points, and to read numerous books like The Courage to Write, and Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway, and Why People Fail, anything that would inch me toward self-confidence.

I also worked on my paralyzing perfectionist tendencies in other areas; I had quit working as a musician in my early 20s because of these tendencies, which made me terrified of making a mistake and kept me from playing with other musicians. But I found a group of musicians who were so encouraging that over a period of about 10 years (yes, that long!) I learned to sing and play with not only confidence, but joy.

When I decided to publish The Taste of Hunger I also decided to try to have that same experience with writing: the last frontier so to speak. I resolved to fall back on my community and friends when the demons struck. When I was terrified the novel was dreadful and that was why I hadn’t heard back from the publisher, rather than wallow in a deeper and deeper pit I sent the book to two friends who I knew would be kind but fair, and who would tell me if it needed more work.

When I hit that terribly anxious phase after the proofs are in and before the book is out, when all I could imagine was terrible reviews, I spoke to my managing editor, publicist and friends about my fears, enlisting their support. And I invited everyone I knew to the launch in a spirit of sharing and celebration and above all gratitude for the support they’d given over so many years.

I also signed up for a meditation course the month The Taste of Hunger came out, which is offering different strategies for dealing with 4am monkey mind. And this time around I am having a better time of it. The most important thing, that readers love the book, appears to have happened, and that is worth every anxiety, every slain demon.

Did you ever think about giving up on writing? Why didn’t you? How did you move past that point and recommit?

I thought about quitting this novel more times than I can count but what always drew me back was that I loved these characters and couldn’t let them down. And I had wonderful friends, who read all its incarnations and wouldn’t let me abandon the book.

As for quitting writing, which is a different thing, I’m not sure I ever got to that point for long. At the very least I knew I would always journal. I have the kind of mind that has to write something down before I fully understand, perhaps even fully experience, it.

Also, I like all the physical elements of writing: my favourite fountain pens (of which I have quite a few) biting into a clean page, even if it’s just to make a to-do list; the ticking of the keys under my fingers, even if it’s just saying “Today I did laundry.”

I am enjoying answering these questions enormously for just that reason: I get to type and in the process, discover what I think! One of the most important distinctions for me is between writing and publishing. In the writing stage I remind myself I can write whatever I want: I don’t have to publish it. This leaves me free to explore and loosens up at least some of the anxiety, allows me to enjoy the process.

I am thrilled to have published but if I never publish another word I don’t see giving up these other pleasures. (But the supreme pleasure of reader response will most likely make me try to publish again, of course!)

How are you feeling about your writing practice right now?

Well, in the immediate aftermath of bringing out a book, the mind is a snarl of ego: moments of great joy (good review) and anxiety (people will know how I think: aaaggghhh!), that kind of thing. Not the most conducive mind set for the huge work of embarking on a novel.

So at the moment my writing practice consists of picking away at various projects to see which one sticks. I write emails to myself with cryptic messages like: perhaps the mother has emphysema. Then I try to figure out what I was talking about.

I’m going over old stories and essays, rewriting and sending them out. (In 2021 one of these essays, “Black Diamond,” won the WGA Jon Whyte Memorial Essay Award.)

I’m also looking over what got culled from the novel to see what it might become. Keeping my toe in the water until my mind settles. I’ve learned to be gentler with myself, to trust that my love for writing will always draw me back, so I’m not beating myself up for not being halfway into my next project.

What’s been your favourite part of finishing and publishing your books?

My absolute favourite part has always been the reaction of readers, and of authors I admire. Robert Kroetsch went out of his way to tell me several times how good The Quick was. There were a few times when complete strangers came up to me to tell me how much one of the stories moved them. That is heaven.

Response to The Taste of Hunger has been a delight to me. Rona Altrows, a wonderful Calgary author, told me she was so worried about the two characters Marie and June that she got up from her bed and read until 4 a.m., until she’d finished the book. Another friend who admitted that she usually reads only 10 minutes a night, to drop off to sleep, told me pretty much the same thing: the first night she read 30 minutes, the next an hour, and the next day she poured a cup of coffee in the morning and read through the day until she was done.

And herein is the caveat to what I said earlier about writing being different from publishing: you can write in your room and never let your work see the light of day, or expose it to strangers. This is what I was doing when I was too afraid to sing with others. But now that I’ve found the courage to sing with others, there is no greater pleasure.

And the same thing goes with finding the courage to publish: there is no greater joy than hearing that someone loved your book, loved the characters in your book, as much as you do.

Do you ever get “stuck” or find yourself avoiding writing? If/when that happens, how do you get yourself unstuck?

I love to do writing exercises. I own dozens of ‘how-to’ writing books, books of prompts. Even though I don’t think of myself as a poet, during one dry spell I did every exercise in several ‘how to write poetry’ books, especially loving the more rigid forms like the villanelle or sestina. I have no intention of ever trying to publish them, the writing was for pure joy, and that shook loose the anxiety that is usually what is keeping me from the page.

Another trick I use is to read writers on writing, reconnecting with my tribe, my chosen family. Either what they say is so apt it inspires me, or so hair-brained it drives me to the page to prove them wrong! I also find it helps to have a subsidiary passion; mine is music.

In my office and whenever I’m on a writing retreat, I have my guitar with me. If I get hopelessly stuck, I turn my back on the writing and pick up the guitar. And then after a while, my project sneaks up on me, taps me on the shoulder and offers some new insight. I also love cooking, which gives the kind of beginning to end experience that is denied you when you’re working on a long project like a novel.

When I was at university and completely stressed out by deadlines, exams, and later, marking, at Christmastime I would refuse invitations to make antipasto with a group, and instead make an enormous batch all by myself: it took all day, but the chopping, stirring, bottling were all so satisfying, almost cathartic, not to mention having gifts for people at the end of it. And that was the point: there was an end to it.

This may sound like avoidance but again, what I find is that if I engage my conscious mind in tasks like these, my unconscious mind loosens up, starts to come up with solutions to the problem in the text.

What’s your favourite book about writing or writing craft?

More than one: I have a kind of addiction to them! But I will narrow it down to three: Jack Hodgins’s A Passion for Narrative was a mainstay for years, as was Janet Burroway’s Writing Fiction. For a number of years I taught from Burroway’s Imaginative Writing which is also excellent, exploring the genres of fiction, creative nonfiction, poetry and drama.

Hodgins gave excellent advice not just to read the exercises but to do every one, and I did. He also made an observation that I have reminded myself of many times: If you are not afraid to write this book, it’s probably not the book you’re meant to be writing. That fear of letting down your book is an essential aspect.

Whom do you consider your mentor(s)?

I don’t really have what I would consider long term mentors, but a few people have been deeply important to my writing life.

Edna Alford at The Banff Centre during the five week retreat was so encouraging and insightful. D. M. Thomas, with whom I worked through the Humber College, told me, after I got a particularly distressing rejection: “I’m telling you you’re fucking good. Fuck everybody else.” Gotta love that man!

Alistair McLeod, whose writing I so revere, told me after reading a section of The Taste of Hunger: “Well, you know how good you are.” Which effectively robbed me of speech for the rest of the interview.

Louis de Bernieres wrote a letter of recommendation for publishers I might want to submit to, which I couldn’t bear to part with because I could look at it every so often to remind myself there were people out there who believed in my writing. Yet even with encouragement like this it took me years to find the confidence to finish the book and submit it to agents and publishers. See my above comments about therapy…

What are you working on now? How are you feeling about it right at this moment?

The biggest thing I’m working on is going over the material I had to cull from the novel for it to take its current shape.

Originally I had written three narrative lines in three different time frames, so when I decided to focus on just one of those lines in The Taste of Hunger, I ended up with a lot of material on the cutting room floor. But there are characters I love deeply who wound up there too, so I am now going through the discard pile looking for scenes, settings, situations, that still move me.

Now that this narrative line is unhooked from The Taste of Hunger themes, I am free to do a lot more exploring into what the new story might be about. It will still require a lot of new material, but I do love revisiting these old friends.

What I especially like is that much of the ground work has been done: I know the main characters, a fair bit about their situation, so I’m not starting completely from scratch.

I’m the kind of writer who can find the rough draft stage painful but who loves the rewriting stage, and what I’m doing is kind of in between the two. So I am part hopeful, part trepidatious, but overall looking forward to digging back in.

What advice would you have for writers who do really want to finish a book but just haven’t been able to get there yet?

One of the most important things I did, apart from therapy, was to surround myself with friends who were fine writers and who were, in spite of their own anxieties, finishing and publishing books.

I stopped getting together with people who only talked about writing, mostly about how hard it was. Of course it’s hard! All the worthwhile things in life are hard and require effort and sacrifice.

But watching as friends conquered their own demons and experienced the joy of holding their books in their hands made me want to do the same, and to believe I could.

And equally important, especially as a woman, was the decision that if it was selfish to carve out time for my writing, then so be it: I would be selfish. This is a tough attitude to maintain when you don’t publish anything for years, but a novel takes years. And in case I haven’t made myself entirely clear: it is SO worth it!

BUY THE BOOK:

In Canada, you can buy Barbara’s novel, The Taste of Hunger here or here.

In the US, the book is available as an e-pub via Barnes and Noble or on ye olde Amazon.com here.

Outside of North America, contact the publisher directly here.

The Quick is also available as an e-pub here.